Industry groups across North America were relieved that the Canadian government took steps to end the railroad work stoppage on Aug. 22, which economists had warned could cause billions of dollars in damage to the country’s economy if not resolved quickly.

“Fertilizer Canada thanks Minister Steven MacKinnon and the federal government for their swift action to resolve the rail labor disruptions and get our trains moving,” said Karen Proud, the trade group’s President and CEO, in an Aug. 22 statement. “We are pleased to see the government’s acknowledgement of the need for short- and long-term solutions and its commitment to investigating the issues leading to the dual rail strike.”

While analysts were split on how much the disruption would cost the economy, most warned that the indirect damage would grow over time, though that impact is difficult to measure.

“The economic harm will extend well beyond the C$1 billion ($732 million) of goods that are transported by rail each day,” Goldy Hyder, CEO of the Business Council of Canada, said in an email to Bloomberg. “It will lead to billions more in lost revenue from goods that won’t be sold, lost wages of workers who won’t be able to do their jobs, and the potential for lost contracts from international shippers and consumers.”

A two-week lockout would shave as much as C$3 billion from the country’s nominal gross domestic product, including a C$1.3 billion hit to labor income and a C$1.25 billion loss to corporate profits, said the Conference Board of Canada.

Moody’s puts a higher price tag on the stoppage, saying it could hit nominal GDP by as much as C$4.8 billion over 14 days. To make a noticeable dent in the economy of the US, Canada’s largest trading partner, the strike would have to go on even longer, Moody’s Economist Brendan LaCerda told Bloomberg.

Analysts said the economy could face deferred sales, growing stockpiles of inventories, and goods shortages, as well as waning business and consumer confidence the longer the disruption lasts.

Some companies have shifted to ports in the US in preparation, already impacting domestic railway earnings. CN lowered its annual guidance in July and its CEO Tracy Robinson told analysts there was a sharp reduction in international volumes.

“Customers have a choice on where they get their goods from,” said Greg Moffatt, Executive Vice President of the Chemistry Industry Association of Canada. “If the supply chain they’re exposed to on the Canadian side is not reliable, they’ll look to modify that supply chain.”

With more than 90% of Canadian grain moving by rail, grain futures rose slightly in early trading on Aug. 22 as traders assessed the impact. The shutdown will have “ripple effects” across the continent, “especially given uncertainty toward potential strikes at US ports and given soaring global shipping costs driven by avoidance of the Red Sea and Suez Canal,” Bank of Nova Scotia Economist Derek Holt said in a note to investors.

“The indirect effect on the economy would likely be much larger, particularly if the labor dispute lasted longer than a week,” Andrew Grantham, an economist with Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, wrote in a report to investors. He sees a 0.1% hit to real monthly output growth if the shutdown lasts one week.

The harm to indirectly affected industries is a big reason why many economists did not expect the strike to last long. “The fact that the costs of shutting down Canada’s railroads are so huge makes it less likely that disruptions will last too long, with government likely to step in and order a return to work relatively quickly,” Claire Fan, an economist with the Royal Bank of Canada, told Bloomberg.

According to Benjamin Reitzes, a rates and macro strategist at Bank of Montreal, a “very rough estimate” of the impact of the strike would be a 0.1% hit to monthly GDP growth for every week the action continues. “The longer it lasts, the worse it likely gets,” he said, adding that the impact depends on how prepared businesses are for the disruption.

While some industries that depend on rail can switch to trucks, this is no easy feat. A typical freight train holds the equivalent of 300 trucks and changing transport modes typically comes at a premium of as much as 20%, said Scott Shannon, Vice President of transport firm C.H. Robinson.

“Trucking rates could spike because a whole lot of freight would have to find another way to travel,” he said.

“There is no plan B,” added Wade Sobkowich, Executive Director of Western Grain Elevator Association. “There’s nothing that compares to rail in terms of moving the volumes of grain that need to move at economical rates.”

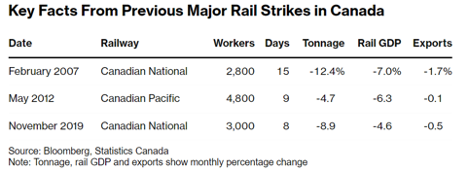

To be sure, some of the economic pain is likely to be reversed when the trains start running again. Bloomberg looked at recent rail strikes in Canada, and though none featured a simultaneous shutdown of Canada’s two rail giants, the impact on the country’s output has historically been limited.