A deal allowing Ukraine to export crops from key ports via

the Black Sea was extended for two months as of May 17, according to Bloomberg,

citing Turkish officials. Russia has threatened to withdraw from the deal if

obstacles to shipments of its own crops and fertilizer were not removed.

However, Ukraine said Moscow was purposefully slowing the pace of exports and

the corridor was now nearly empty, with no inbound ships cleared since early

May.

Exports of most Russian fertilizers were climbing back to

pre-war levels just as President Vladimir Putin’s negotiators made removing

obstacles to the trade a key priority in talks to extend a Black Sea

grain-passage deal.

After total shipments abroad plunged about 15% last year,

most nitrogen and phosphate fertilizers are flowing abroad at close to the

level before Russia invaded Ukraine, according to representatives from some of

the country’s biggest exporters.

Potash and ammonia are the only nutrients still below the

volumes seen prior to the war, sources said, asking not to be identified as the

information is not public. With overall fertilizer exports still lagging 2021

levels, the matter was a key sticking point in negotiations over a grain deal.

Putin’s government has warned that it may withdraw from the

Black Sea Grain Initiative, –

which allows grain shipments from Ukraine – if demands to remove hurdles facing its own food and

fertilizer exports are not met.

While fertilizer companies have not been sanctioned due to

their importance for global food security, Baltic ports have practically

stopped handling Russian fertilizers, contributing to a decline in shipments.

An exodus of global shipping companies from Russia has also made it harder to

send goods abroad, while some international banks and insurers have steered

clear from its deals.

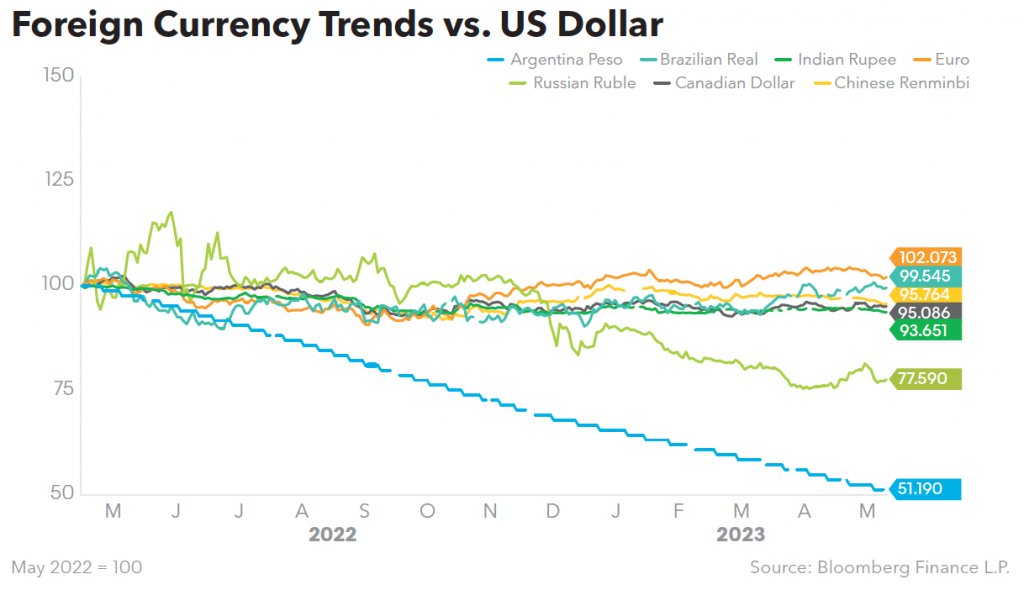

Since the start of its war, Russia has been directing more

of its fertilizer shipments to “friendly” states, including India. Some of its

logistical issues in getting the goods out of the country now appear to be

easing.

“On top of the new ports that are built to handle capacities

instead of Baltic countries, Russia now has a lot of own spare containers due

to reduced international trade,” said Elena Sakhnova, an independent analyst.

One of the nation’s largest container companies, GlobalPorts, offers its

services for fertilizer makers at a good price, she said.

Other industry observers have also noticed the uptick.

Imports of urea from Russia have risen in nearly all European countries, with

the strongest increases in France, the Benelux region, Germany, Italy, and

Spain, according to Lars Rosaeg, Deputy Head of Yara International ASA.

Russian exporters are still facing some issues, however.

Potash sales were down 9% from last year’s level in the first quarter of 2023,

according to Bloomberg Intelligence. Ammonia exports have also been hurt,

as the pipeline that runs from Togliatti, near the Volga River in Russia, to

Ukraine’s Odesa port was shut down because of the war. The link has been a key

subject in recent grain talks, with Russia demanding that it be re-opened.

Part of the issue is that the country has limited

fertilizer-shipping capacities at its own ports, estimated at 17 million mt/y, according

to data from the Russian Fertilizers Producers Association. In 2021, Russia

exported 38 million mt of fertilizers, mainly via Baltic countries that have

now practically stopped working with Russians.

Plans are already underway to expand Russia’s port capacity,

with EuroChem Group AG building a transshipment terminal near St. Petersburg,

which was planned to start next year. Togliattiazot JSC is building a port in

Taman, opposite Crimea, which should begin operations this year and replace the

Togliatti-Odesa pipeline.

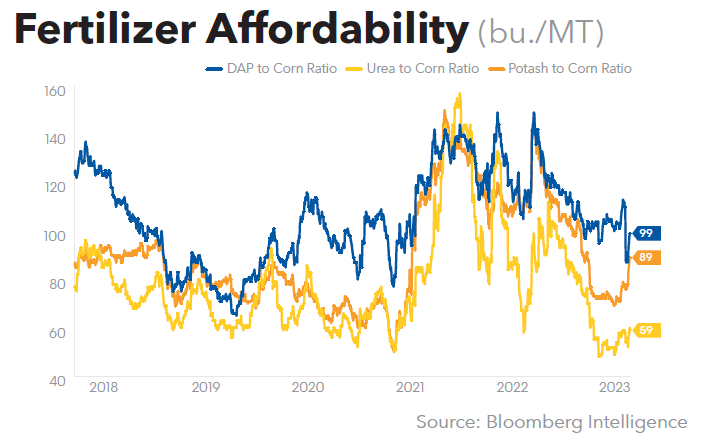

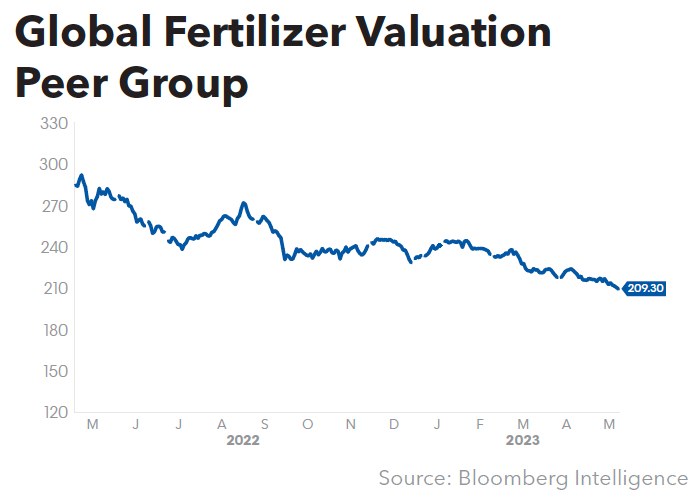

Despite export volumes taking a while to recover, most of

Russia’s fertilizer industry has hardly struggled financially. Shortages pushed

some nutrient prices to record highs last year, and are still well above

pre-war levels.

“Domestic sales are strong, exports didn’t come to an end

and prices offset the possible export losses,” said Sakhnova. “With some

exceptions, Russian fertilizer makers made record profits last year.”